Interlude: The need for storytelling and the relational in an age of isolating and overwhelming dystopian information

How to come back together in what we’re seeing, feeling, and doing

Hello, good morning, good evening, good afternoon! This week’s essay is in its own way a continuation of The Expanse series, but it’s different enough that I chose to title it as an interlude. I think it will serve as a lovely hinge piece to the material I have coming up, as I begin to wind down about the apocalypse, dystopia, and imagination and start to turn my attention towards hyperreality and digital life. As always, this essay will remain free and comments are open to all, but if you haven’t yet committed to a paid subscription, I would truly love to have your support. If you’re enjoying these long-format meanderings, every single contribution helps me get that much closer to carving out the time I need to build them.

Note: I will probably re-record this audio at some point, but I wanted to have it available at the time of publishing. I have to do this in one take because I don’t have audio editing skills and I don’t have time to learn them lol but! I generally do alright so I’ll give it another go, later on.

Our society is much more interested in information than wonder, in noise rather than silence…And I feel that we need a lot more wonder and a lot more silence in our lives.

–Mr. Rogers

People have come to associate apocalypse, revolution, and resistance with a particular kind of violence; as acts of war, combat, or bodily harm. But we have to talk about and include other forms of resistance, revolution, and violence that may seem “softer”, but which have as much impact, if not more, over time. Mr. Rogers is never really credited for being an activist, but he is, and that's important—there he is, this soft-spoken man, speaking directly to children from a make-believe world about deeply profound, world-changing things. Things even parents need to hear. Things we all need to hear. He and his words are gentle, like a breeze or a brook, but ultimately world-building in scope and scale.

I think most people would be better able to see how they can be part of an anticapitalist decolonial movement if they understood how their skills, strengths, and knowledge contributed to not just the dismantling of something (apocalypse, destructive) but the building of things as well (apocalypse, revelatory); not the least of them being the need to connect to one another through the power of story.

Because we’re already well entrenched in dystopian times, there’s no need to dwell on nihilistic storylines, whether fictional, speculative, or the news. Who can tell the difference anymore? The spectacle dazzles and desensitizes. The hyperreal disables our ability to stabilize ourselves on solid ground. I'm not suggesting we turn away from the realities of the world we live in. There are very real mortal and material conditions to address. This is more about how we no longer need to predict a world gone wrong, as everything is going wrong all around us. The failings of society to pay close attention to and heed the warnings of authors, philosophers, thinkers, spiritualists, and storytellers who have long cautioned us against our collective hubris have led us to this climactic chapter of humanity’s epic novel.

I think the pain comes in part from the knowledge that we're not the ones who wrote the present future we’re living in. This story isn’t one we would tell or wish for ourselves. It was drafted, sold, and held in trust by just a few people with billions of dollars writing a singular timeline for billions of people. Then, they made us all complicit by making it nearly impossible for us to opt out, by sowing division among us, by severing us from the land and each other. I don't want to step into a trompe l'oeil painting of a world that doesn’t and couldn’t exist, an illusion of naivete in which everything magically turns out ok. But I am willing to face whatever comes, as hard as it might be, to make my surrounding world as better a place to live as I can. To me this is the embodiment of tangible hope, born of the desire and the need to break free from despair; the kind of hope that grows from roots plunged deep in the earth.

It’s time to wrest the narrative away from those who divide us and set the world on fire for profit. It’s time for us to reclaim our birthright as knowledge-keepers, culture-bearers, relational and experiential humans; connected with one another. It’s time for us to reconnect to story and build the future we want to see. But for us to do that, and to do it well, we're going to have to unlearn, and learn, a lot about what we’re telling, and about how we’re listening; about giving and receiving; about dreaming.

There is a certain hypercapitalist drive to be informative in an age of digital media and corporate owned app-based social media. Information is a product, and it has been for a very long time, since the rise of the prolific and cheap penny press newspaper in the 19th century. I often think about the reduction of the English language, which both expanded and contracted as England colonized the literal planet. In its acquisition of goods, culture, people, and artifacts it stole language, as well; folding in what we would later call “loan words” as if languages had been generously offered to their colonizers and not ripped from their contexts within culture and place. Because this expansion was driven by the mechanisms of capitalism, everything had to become more efficient to be improved; improvement being the term for the development of land for profit but inevitably, the development of anything for profit—both material and ideological. The prevalence of the telegraph, which required brevity and exactness of language, was the literal precursor to the internet. The limited word and line count of the daily, and seduction of the catchy headline, paved way for contemporary clickbait that undermines facts in favor of shock and outrage. The emergence of prolific postwar advertisement echoed the persuasive rhetoric of early 20th century propaganda art so well that eventually, the visual language of advertisement became inherent subtext to our consumerist culture. And now, postmodern memeification of bigger, more complex ideas has lead to the collapse of nuance, propelling international misinformation and disinformation campaigns around politics and political ideology. Sensationalism sells us, and the spectacle controls us.

Recently, I returned to Walter Benjamin's The Storyteller, in which he critiques the rise of information over the value of storytelling; the way information has superseded the story. Reflecting on this, I recall the kind of knowledge and idea-sharing that is within community and personal, relational and experiential (ancient, found globally, exchange-based, human-centered, our primary way of learning since time immemorial) versus the kind that is within subject and object, expository and journalistic (contemporary, Eurocolonial, commodity-based, consumer-centered, our primary way of learning only within the last 500-200 years depending on where we are in the world). Alongside this difference in craft is a difference in reception—how we read. We’ve been trained to read quickly, to skim and scan for the most relevant information as opposed to spending time with a story and the wisdom it contains or the relationships it creates. Information contains facts or opinions in isolation, out of context with larger circumstances, relationships, environments, or histories. What can be learned from this to change and shape our lives with what we’ve learned? This is a thing that happened. Or, This is an opinion or an idea I have. We consume. The next thing pops up. We consume. The next thing pops up. We consume. But when do we process? When do we integrate? When do we act to effect change?

Storytelling, on the other hand, contextualizes information to make it relational, circumstantial, inherently relevant to the human and everyone the human knows. A story is located in time, place, environment, culture, spirituality, language, and community. Stories take time to tell properly, they can't be rushed; they create space for silence, and reflection. As carriers of knowledge, wisdom, experience, and relativity storytelling requires active and meaningful participation from listeners, because they illustrate and demonstrate actions we can take towards right relationship and better ways of living and being together in the world. This relativity and relationality is why so many stories have lasted the test of thousands of years; why traditional ecological knowledge from around the world is still relevant; why global Indigenous lore, as well as European and diasporic European folklore, all contain animist wisdom about interacting with our world and the cosmos that can be understood today—even in the context of a world that has separated us from these ways of looking and seeing. Stories are an antidote to severance.

Though Benjamin has a few things to say about the problems of the novel and the short story, it’s hard for me to deny with my 21st century lens that it is precisely the novel and the short story that has given isolated, severed, westernized humans access into the incubative and reflective space of the story to understand better, relationally, some of the hardest issues of our time. As early as the late 19th century, science fiction, speculative fiction, and fantasy have been some of the most successful carriers of those stories, embodying philosophy and protocols for how to live a better life as well as cautionary tales on how to avoid dystopia. We're compelled by these stories because of the humanity that we see portrayed within them and the empathy they ignite within us. We're emotionally carried through the grief, trauma, and wounds of industrialization and isolation to regain a sense of clarity and even hope. The portrayal of humanity in the face of the extraordinary is motivating.

I think in some ways, the science fiction or speculative fiction novel inherently portrays a kind of optimism for the survival or longevity of humanity by projecting our existence thousands of years into the future. Such a timespan seems to allow for humans to figure out a few things. One author who comes to mind is Ursula K Le Guin, who unflinchingly confronts, and asks us to question, the systems of humanity’s governance, societies, and culture that influence and harm us today by creating stories that are both windows into other worlds, and mirrors of our own. A lot of people like to reference The Dispossessed because of its story around the disparity between Anarres, a collectivist anarchistic society and Urras, an individualistic capitalist society. It’s a good example of how Le Guin asks us to consider anarchism as an option to the society we’re already familiar with; as well as a call to be critical of any ideology that is ultimately corruptible. But another novel I think a lot about is The Left Hand of Darkness, which describes a future in which race, gender, and sexuality are more fluid and androgynous than our westernized situations tolerate; and in which Le Guin attempts to combat the alienation and individualism of capitalist society by presenting the alternative: a tolerant, integrated society with integrity, compassion, empathy, and care.1

The way Le Guin wrote this novel matters. She employs a multitude of narrative devices including in-world sources in mythology, folklore, religious documents, diaries, reports, and field notes to describe the world. This method draws out subtle details that are rich in diversity and perspectives, and which allow differences of perspective or culture and even contradictions to appear. At times, the narrative even seems to break free of linear time. It’s about how there is no singular objective reality or truth. It’s about the way we could live our lives together that depart from the oppressive narratives and ways of life that have been prescribed to us by those who don’t have our best interests in mind. It’s about how conflict and betrayal may still occur, but when we imagine better for our multitudinous intersecting worlds and we prioritize relationships and connectivity, we learn so much more about what’s possible and begin to bridge those divides.

We must find ways to return to the relationality and reciprocal exchange of story. Information is disaster capitalism's propaganda. Information is the realized imagination of apocalypse and prescriptive dystopia that draws us further into the data of despair. In contrast, stories and storytelling encapsulate our collective imagination to not just think about, but act to build something better; to write a new prescription; to lay better plans; to relentlessly pursue happiness, joy, and mutually assured prosperity. Storytelling is a path of intimacy, a way to move together, varied and flawed and glorious. We have overlaps to bond over, and differences to learn from. Conflict is inevitable, but no matter who and where we are, we all have lives we've lived, knowledge to bring, and stories to share.

Further reading and listening for those interested:

Katie Crowson, The science behind Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, Science Museum, 2023 (online)

Maria Popova, Walter Benjamin on Finding Wisdom in the Age of Information and Storytelling as the Antidote to Death by News, The Marginalian, 2015 (online)

Mary Shelley, Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, England, 1818

Mr. Rogers' Neighborhood, 1968-2001

The Storyteller by Walter Benjamin—Summary and Analysis, Mostly About Stories, 2019 (online)

Ted Chiang, Story of Your Life (originally published in Starlight 2, November 1998), Stories of Your Life and Others, Tor Books, New York, 2002

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Dispossessed, New York City, Harper & Row, 1974

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Left Hand of Darkness, New York City, Ace Books, 1969

Ursula K. Le Guin, The Word for World is Forest (novella originally published in Again, Dangerous Visions edited by Harlan Ellison, Garden City New York, Doubleday 1972), Berkley Books, 1976

Walter Benjamin, The Storyteller, Reflections on the Works of Nikolai Leskov, 1936

At a later point in my meandering path of essay topics, we'll get into The Name for World is Forest, which takes place in the same universe as The Dispossessed and The Left Hand of Darkness, but which has strong anti-colonial and anti-military themes and is in part about dreams and animism.

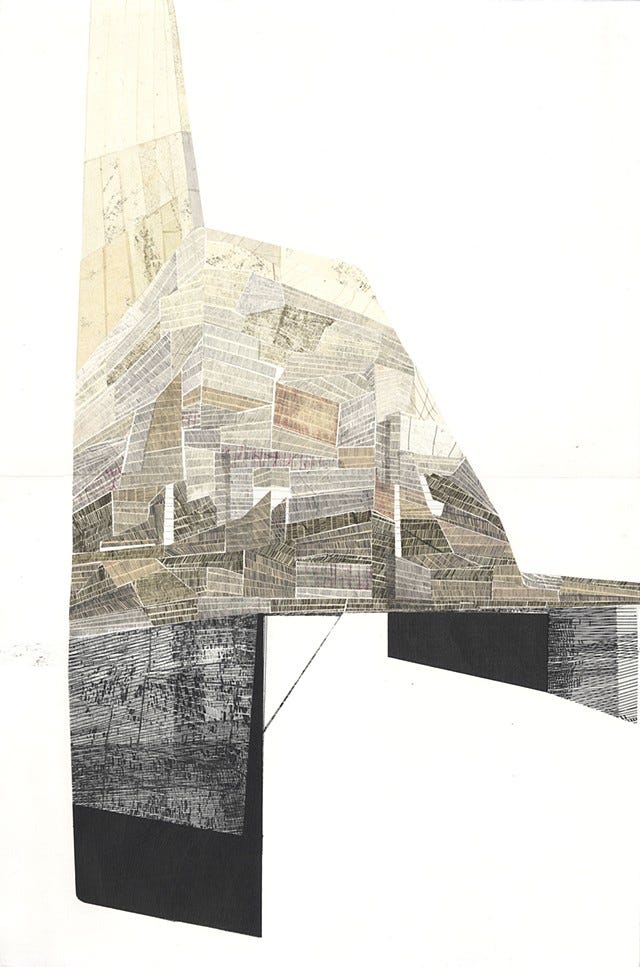

2 A footnote about Kim Van Someren’s work:

I’ve written about printmaker Kim Van Someren on a few occasions but most recently here in my essay Transformative Machines for Someren’s 2020 exhibition, The Slant of Line, at J. Rinehart Gallery in Seattle. In it, I muse on the humanity of her architectural forms, and how I imagine these forms being a sort of empathy- and compassion-centered way of approaching shelter and protection; as communal and liberatory in their precarity and their intimacy. While writing this essay you’re reading today, on storytelling; I figured that if there were any architecture I could imagine for Ursula K. Le Guin’s worlds in the Hainish Cycle, these structures would be it. Many thanks to both Kim and Judith for generously sharing this piece as an accompaniment to today’s essay.

Here are a few excerpts from my former piece, Transformative Machines:

“...These structures and mechanisms contain a greater feeling of a protective force, of sheltering, of dynamic forms to hold those within while weathering the terrain on which they cross, to withstand the outside uncertainties they face…

…A phrase jumps out from Kim’s notes, structures stand, colossal and capable. And I see my own note next to it, abandon engineering and I believe it means to teeter dangerously at the precipice of whatever is to come after what we have built is gone. A slant of line, leaning into the unknown; these are the towers, breaking free.”

Great piece, Sharon! Of course, I love Mr. Rogers, having grown up with him. His name should be mentioned in the same sentence as the Dalai Lama, et al. And I love rereading those two LeGuin novels. I need to dig into the Benjamin info/story, though…that one’s new to me.

thank you, John! Benjamin's essay is linked in the resource list, you can download the pdf. it's a review he wrote, but there's all thus other great stuff contained within. I'd love to hear what you think!